Sunday, July 23, 2023

First Congregational Church of Cheshire

© the Rev. Dr. James Campbell

Romans 8:12-25

So then, brothers and sisters, we are debtors, not to the flesh, to live according to the flesh— for if you live according to the flesh, you will die; but if by the Spirit you put to death the deeds of the body, you will live. For all who are led by the Spirit of God are children of God. For you did not receive a spirit of slavery to fall back into fear, but you have received a spirit of adoption. When we cry, “Abba! Father!” it is that very Spirit bearing witness with our spirit that we are children of God, and if children, then heirs, heirs of God and joint heirs with Christ—if, in fact, we suffer with him so that we may also be glorified with him. I consider that the sufferings of this present time are not worth comparing with the glory about to be revealed to us. For the creation waits with eager longing for the revealing of the children of God; for the creation was subjected to futility, not of its own will but by the will of the one who subjected it, in hope that the creation itself will be set free from its bondage to decay and will obtain the freedom of the glory of the children of God. We know that the whole creation has been groaning in labor pains until now; and not only the creation, but we ourselves, who have the first fruits of the Spirit, groan inwardly while we wait for adoption, the redemption of our bodies. For in hope we were saved. Now hope that is seen is not hope. For who hopes for what is seen? But if we hope for what we do not see, we wait for it with patience.

In the remarkable opening of her book, Here If You Need Me, the Rev. Kate Braestrup told the story of the tragic death of her husband, Drew, a state trooper killed in a car accident while on duty. At the funeral home, the funeral director tried to help the family maintain that safe distance from death. But Kate would have none of it. Instead, she decided that she would do what humans have done for millennia. As a final act of love, she would personally prepare her husband’s body for cremation and burial. The funeral director tried to dissuade her, but she was undeterred. So, the staff brought her a basin and soap and wash cloths. And then, she lovingly and methodically washed the broken body of her husband.

I read this book many years ago, but that scene has never left me. At first, I admit, I was repulsed by the idea of what she did. I couldn’t imagine myself doing such a thing. But then I realized that my own reluctance had everything to do with a cultural conditioning that denies pain and suffering and death.

This cultural conditioning is exceedingly strong. And it plays out in innumerable ways. We worship youth and vigor. We hide age and illness. And because we are so afraid of dying, we pretend as if we won’t. As the great Loretta Lynn sang on her last studio album before she herself died: “Ever’body wants to go to heaven, but nobody wants to die.” Well, ain’t that the truth?

But we know we will. And it is one of the counterintuitive pillars of our Christian faith that in order to find hope, we must face our fears; we must stay with our fears, until they are transformed. There is no Easter without Good Friday.

But the problem is that at this moment, Good Friday seems like it will never end. This 21st century, to date, doesn’t seem to have much Easter in it at all.

Scientists say that this is the hottest the earth has been in the 125,000 years. Canadian wildfires, one thousand miles away, turned our Connecticut skies apocalyptic for days on end. Air quality alerts forced us indoors just when we wanted to be outside. Raging floods decimated Vermont’s capital and small towns in upstate New York. South Florida neighborhoods regularly flood on sunny days, while insurance companies flee that state. And on and on and on it goes.

Our natural instinct is to turn away. “It’s Sunday, James. Give us a break!” But just like Rev. Braestrup, we need to stay in this moment for a little while. We need to look. We need to lament.

Lament: such an old-fashioned word. Such an outdated idea. And yet, there is an entire book of the Bible entitled Lamentations. It’s found in the Hebrew Scriptures, sometimes called the Old Testament, and is composed of a series of five heart-rending poems that mourn the destruction of Jerusalem by the Babylonians in 586 BCE. In these poems, the writer looks at the calamity full in the face. He accepts human culpability in what has happened. And he wonders where God is in the midst of such a mess.

Lament also finds its way into our New Testament. In his foundational epistle to the church at Rome, St. Paul laments the suffering of Creation as it waits for us humans to grow up into the fullness of Christ. Paul says that the whole Creation groans in labor pains waiting for us to get our act together.

Listen again to his words: “For the creation waits with eager longing for the revealing of the children of God; for the creation was subject to futility… (But) the creation itself will be set free from its bondage to decay and will obtain the freedom of the glory of the children of God. We know that the whole creation has been groaning in labor pains until now…”

So, there it is, as if it were written yesterday – a description of this present moment; a stark view of what human sin does to everything else that God has made. And we need to stay with that stark reality for a while. We need to pause and repent and throw ourselves on the mercy of God.

Lament is the first step and essential step in human transformation. It is the first building block of a vibrant and active faith. It’s just not the whole building. Instead, as Paul says in Romans 8: “In hope we (are) saved.”

But what does hope look like in the midst of the constant bombardment of predictions of doom? Well, some people say that God will rescue us from the messes we have made. They look to the Second Coming of Christ or to the promise of eternal life as an “escape hatch” from a planet in peril. -- But I don’t think of those divine promises as escape hatches. Remember that even Jesus was not rescued from the Cross, even when he prayed “Let this cup pass from me.” He had to go through it. He had to stay with it to get from Good Friday to Easter.

And Paul writes boldly, not of escape, but of the salvation of this groaning creation. And Jesus, our Lord, taught us to pray: “thy kingdom come, thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven.” So, our faith is not about escaping while everyone and everything else suffers. Our faith is about rising up to repair and heal and love and bless this beautiful but broken world.

It’s too late, some say. There is nothing we can do about it, many others say. And besides that, we are afraid. We are overwhelmed. We are in deep denial.

But we are not the first people to be in such an existential predicament. Long before us, faithful people have lived under the crushing brutality of Empire and through hideous decades of war and the cruelty of famine and the specter of disease and the terror of nuclear annihilation. Think of what the faithful in Ukraine are living through right now. And in each of these moments, God’s people have been called to lean into what has been promised, and then to do what you can.

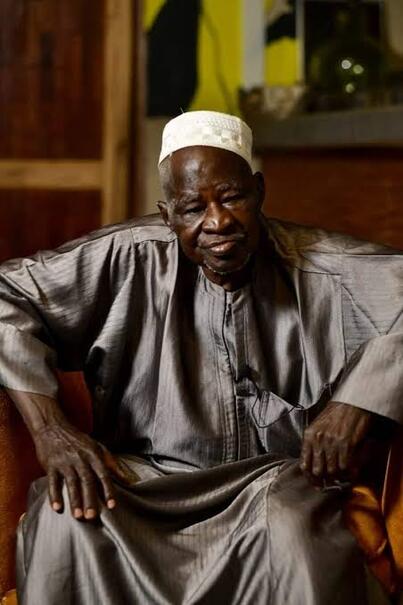

In the 2014 film The Man Who Stopped the Desert, we see what practicing hope can do in the face of overwhelming challenges. Yacouba Sawadogo is an illiterate farmer from the West African nation of Burkina Faso. But this simple man has done more to reverse the ravages of drought, brought on by over-farming, deforestation, and climate change than any Western intervention. Sawadogo’s unorthodox methods have returned 50 acres of harsh desert back into a verdant garden. How did he do it? Well, it was all rather simple.

Yacouba dug something called “Zai holes.” They are much deeper and wider than what is usually used for planting. Then he filled the Zai holes with water-absorbing compost – mostly animal manure. Then he used small stones to create pathways for the rainwater to fill those holes. Then he planted trees and vines and crops in those Zai holes. Whenever it rains, the stone paths direct all the excess water into the holes. And when it doesn’t rain, the compost retains the dampness necessary for the plants to thrive. In the beginning, the other farmers mocked him for his hopefulness. Government officials tried to dissuade him. But Yacouba persisted. And now, he and others like him enjoy “food sovereignty.” Because he was undeterred; because he put hope into action, the words of Prophet Isaiah are fulfilled: “the desert blooms and rejoices.”[1]

Lament is a necessary first step. And frankly, fear can be a great motivator. But lament and fear are not our final destinations. Because continual lament makes us self-centered. And constant fear paralyzes us, making us believe the poisonous lie that there is nothing we can do. But friends, we are the children of God. We are joint-heirs with Jesus Christ. We have been given the power of the Holy Spirit. And the fruit of that Spirit is HOPE IN ACTION.

How will you make that true?

[1] Isaiah 35:1

RSS Feed

RSS Feed