November 19, 2023 – Thanksgiving and Consecration Sunday

© the Rev. Dr. James Campbell

Luke 17:11-19

On the way to Jerusalem Jesus was going through the region between Samaria and Galilee. As he entered a village, ten lepers approached him. Keeping their distance, they called out, saying, “Jesus, Master, have mercy on us!” When he saw them, he said to them, “Go and show yourselves to the priests.” And as they went, they were made clean. Then one of them, when he saw that he was healed, turned back, praising God with a loud voice. He prostrated himself at Jesus’ feet and thanked him. And he was a Samaritan. Then Jesus asked, “Were not ten made clean? But the other nine, where are they? Was none of them found to return and give praise to God except this foreigner?” Then he said to him, “Get up and go on your way; your faith has made you well.”

Next week, I will spend four days at the Episcopal Monastery of the Holy Cross on the banks of the Hudson River. I’ve been going there for years now, and count it as one of my favorite places, anywhere.

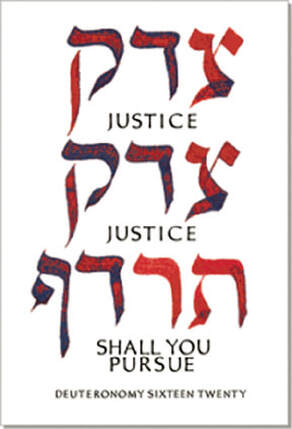

At Holy Cross, I have done both silent and guided retreats. One of those was on the physicality of prayer. In other words, how you use your body when you pray. Another one was on the feminine aspects of the divine, a topic I have a long-standing interest in. But the most memorable guided retreat was the one I did on writing an icon - which is how one refers to the process of painting one. You “write” an icon.

In addition to the history and theology of iconography, we learned technique. I learned that despite their vibrant appearance, icons are made up of layers and layers of very thin, watery paint. And because the layers are thin, it takes a long time to write an icon and requires a great deal of patience – which is actually one of the main points. That repetitious action, done over a long period of time, is supposed to free your mind and open you soul. Icon writing is a form of prayer; a way to make space for God.

Well, I can tell you that in the beginning, the exact opposite happened to me. I was worried about not knowing how to paint. I was self-conscious and sure that others would do better than I did. I wondered what had ever possessed me to sign up for such an experience. But eventually, as the hours and days wore on, that slow, deliberate repetition began to open something up inside of me. It made space. The light got in. And I began to change.

Here is what I mean by that. One day, I was in the monastery chapel, listening to the monks chant the Psalms, which usually would bored me stiff, when suddenly I was vividly conscious of being part of the great sweep of Jewish and Christian history and devotion. Later when I was sitting quietly with the other participants in the common room, reading my book and sipping a cup of tea, I was suddenly connected to everyone there – and the communion of saints made sense to me for the very first time. Over delicious meals, I was somehow wide awake to the taste and smell and feel of the food in a new way. And what’s more, I was aware of the food becoming fuel in my body. It was almost mystical. And all of that openness made me feel alive. And all of that aliveness made me feel deep GRATITUDE. I remember walking around the monastery grounds giddy, just for being alive.

I wish I didn’t need a monastery and an icon writing class to hook more easily into that kind of transformative gratitude. But the truth is that we are all so busy and frantic and stressful that we need something out of the ordinary to make us slow down long enough to be open so that gratitude can get in.

Jesus was on his way to Jerusalem, where he would be tried and executed. On his way, Luke says that Jesus passed through the region between Samaria and Galilee, which is a strange thing to report since it wasn’t really on the way to Jerusalem. But circuitous routes are so often where the Holy Spirit does her best work.

Jesus entered a village where he encountered ten lepers. And from a distance they began to cry out, “Jesus, Master, have mercy on us!” And mercy is exactly what they needed. They lived desperate lives, sequestered on the outskirts of town. Everyone was afraid of catching what they had. Everyone believed they deserved it, because everyone believed that illness was a punishment from God.

It’s interesting that Luke does not describe the moment of their dramatic healing. Instead, Luke says that Jesus simply told them to go show themselves to the priest to verify their healing. And Luke writes that as they wentthey were made clean. In other words, it was in their movement, in putting feet on their faith, that they were transformed.

Now I imagine that when they realized what had happened to them, they were overcome. And I imagine that adrenaline kicked in and that they ran as fast as they could toward their restored lives. They ran to the priest. And they ran home and embraced their children. They sat down to a meal with their extended families. They slept in tangled with their spouses. Oh, I would have run back home too. I would have never looked back, for fear that it was all too good to be true.

But one of them did. One of them actually stopped and paused. This one, turned around and looked for Jesus. And Luke reports that, understanding what had happened to him and who had made it possible, he began to praise God with a loud voice and prostrated himself at Jesus’s feet and thanked him. And then Luke adds this explosive throwaway line: “And he was a Samaritan.”

And here the story loses all sentimentality we might heap upon it, and it becomes subversive, because everyone hated Samaritans. In a modern retelling, Jesus might say that the one who returned to give thanks was a Muslim Uber driver or an undocumented restaurant worker or a bullied transgender teen. Like those folks, Samaritans were despised because they were the wrong kind of people. But Luke makes this double outcast – a Samaritan and a leper – the hero of the story.

Then Jesus said something rather odd. Maybe it was tongue in cheek; said with a twinkle in his eye: “Where are the other nine? Is it only this foreigner who has returned to give thanks and praise?” Then he looked at the restored man and said: “Get up, sir. Go on now, and enjoy your life, sir. Your faith has made you well, sir.”

“Your faith has made you well.” And at this point, Jesus was no longer just talking about the man’s physical healing because the Greek word for “well” changed to “sozo” implying not just physical health, but overall wholeness, completion, salvation. So, what had changed in this man between his healing and his running back to Jesus that saved him? It was gratitude, given space to grow because he stopped and considered the source of the gift.

I think I got a little of that “sozo” myself when I wrote my icon of the Angel Gabriel; and as I sat in the chapel and listened to the ancient Psalms, and tasted every morsel of food, and was astonished by the sunrise over the Hudson. I was open to gratitude.

You don’t need a trip to a monastery to learn to be open to the miracles that surround us. You just have to slow down and stop long enough to see them. – So, let’s try. Take a look around at this incredibly beautiful room, imbued as it is, with the spiritual energy of 200 years of human joy and sorrow: thousands of baptisms and weddings and funerals; thousands of hymns and sermons and prayers. Isn’t that something? - And if you felt any gratitude for that, we just added a layer of paint to our icons.

And then there are the people in this room right now: to your right and to your left, behind you and in front of you. There is the soft sound of their breathing, and the rhythm of their hearts; the vibrant color of the clothing, the dreams and hopes and wishes inside each of these children of God. And if that makes you thankful, we then, there’s another layer.

And let’s pause for just a moment to consider that somehow this congregation weathered the storm called Covid so much better than most. We are still strong and vibrant and hopeful about our future, and about this church’s ministry to people outside our walls. And there’s another layer.

And now let’s think of all those who will come after us; who will stand on our shoulders; who will think of us and be grateful that we were here; that we were generous; that we laid a foundation for this congregation’s 4thcentury of service for Jesus Christ. And we layer on more love and more hope and more faith and more gratitude, until lo and behold, we too have created a thing of beauty; an icon of gratitude to the One whose faithfulness is new every morning.

Thanks be to God. Amen.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed