TWO SIDES OF THE SAME COIN

First Congregational Church of Cheshire

© the Rev. Dr. James Campbell

John 12:1-8

Six days before the Passover Jesus came to Bethany, the home of Lazarus, whom he had raised from the dead. There they gave a dinner for him. Martha served, and Lazarus was one of those at the table with him. Mary took a pound of costly perfume made of pure nard, anointed Jesus’ feet, and wiped them with her hair. The house was filled with the fragrance of the perfume. But Judas Iscariot, one of his disciples (the one who was about to betray him), said, “Why was this perfume not sold for three hundred denarii and the money given to the poor?” (He said this not because he cared about the poor, but because he was a thief; he kept the common purse and used to steal what was put into it.) Jesus said, “Leave her alone. She bought it so that she might keep it for the day of my burial. You always have the poor with you, but you do not always have me.”

+++

To understand the passage we’ve just heard, we have to back up to a previous and pivotal event. Sisters Mary and Martha had sent word to Jesus that their brother Lazarus, upon whom they depended entirely in that patriarchal society, was very ill. Despite the urgency of their message, Jesus delayed his coming. Jesus delayed and Lazarus died. When Jesus finally arrived four days later, the sisters were overcome with grief, compounded with anger and deep disappointment. But Jesus told them that if they believed they would see, for themselves, the shining glory God. And then he stood outside Lazarus’s tomb, and through his own tears shouted down death: “Lazarus, come out,” he commanded. And Lazarus did.

Today’s scene takes place some days or weeks later. Now the tables are turned and it is Jesus who is standing at death’s door. The religious authorities were after him precisely because he had raised Lazarus from the dead. This was the opposite of “dead men tell no tales.” In fact, this dead man had one heck of tale to tell. It was enough to cause an insurrection. So Jesus had to go.

It was, in this atmosphere of dread and fear, that Jesus sat down to eat with this bes friends. There, at least for a few hours, he would be safe and sound. In the midst of the meal, Mary did a very odd thing. She left the room and returned with a box of nard – a very expensive perfume with a fragrance somewhere between mint and ginseng. Nard was made from a little plant that grew in the Himalayas in far off India. It would have been brought to Palestine by camel caravan, thus its high cost. It was the kind of exotic spice that might have been used to anoint the body of a dead person, in order to mask the smell of decay. Maybe this box of nard was leftover from the time of Lazarus’s death.

Mary knelt down in front of Jesus and opened the box and began to anoint his feet with it. That was odd too. Unlike anointing one’s head as one might do to a king at a coronation, anointing one’s feet would have been understood as a death sign – something one does to a corpse. And then she wiped his feet with her hair.

It’s interesting to note here that in Mary’s actions we see a precursor to Jesus’s actions just a few days later. Mary washed Jesus’s feet with the perfume and then wiped them with her hair. Jesus washed the feet of his disciples with water and then wiped them with a towel. Maybe Jesus was imitating Mary’s act of love.

It was an act of love, but not everyone was impressed with it. Some of those present were no doubt scandalized that an unmarried woman was even in the room with the men. And then she let down her hair – which an honorable woman never did except in front of her husband. And then she touched Jesus’s feet, which was seen as an intimate act, and used her hair to wipe off the nard – another intimate act.

But for Judas, what was far more offensive than any of her actions was the waste of money. And so he protested: “Why was this perfume not sold for three hundred denarii and the money given to the poor?” It’s a good question, actually. 300 denarii was basically a year’s wages. Imagine the good that could have been done with that? What would this church do with an extra $56,000 this year, which is the average American wage? It’s a good question. It’s the kind of question that comes up at every Annual Meeting I have ever attended. So, there’s nothing wrong with the question.

But John adds this detail to let us know that Judas’s motivations were less than noble. He writes: “(Judas) said this not because he cared about the poor, but because he was a thief; he kept the common purse and used to steal what was put into it.” These details about Judas are only found in John’s Gospel. It’s as if John wants us to understand clearly the kind of person Judas was – a traitor and a thief.

In the past when this lesson has come up in the lectionary cycle, I’ve almost always preached about Mary. She’s far more likeable. In addition to that, anytime we can lift up a strong and faithful woman in Scripture, we should. Women have been given the bum’s rush in the church’s history since about the second century. So at Mary, the faithful, we should pause and pay our respects.

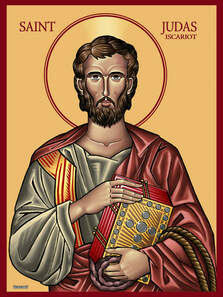

But this time around, I found myself wondering about Judas – the one whom dismisses as a thief and a liar. It’s almost as if John doesn’t want us to look any deeper into this man. Maybe he had a vendetta against him. And so what we are left with is a one-dimensional character, who is easy to hate and convenient to dismiss.

I was intrigued recently to read about something called “The Burning of Judas.” In certain Mediterranean and Latin American countries, it is the tradition during Holy Week to make an effigy of Judas that is publically hanged on Good Friday and then burned on Easter Sunday evening. Before burning, some people beat the Judas figure with sticks or explode it with fireworks. Sometimes this Judas effigy is simply referred to as “the Jew.”

Isn’t that odd, I thought. Except, of course, it isn’t. The Judas figure taps into a deep human need to pass the buck. In Judas, people find an easy target to vent their frustrations and blame for the troubles of the world. It’s not at all unlike what loud-mouthed media personalities do to gay people or black people or Muslims or immigrants. It’s called scapegoating. Judas, then, is a stand-in for those things we don’t like about others, which (by the way) are almost always things we don’t like about ourselves.

But we know that no one in this world is one-dimensional. And we know that surely there was more to Judas than his worst moment and worst decision. Who was he before that fateful kiss of betrayal in the Garden of Gethsemane? Who was he before he began to steal from the treasury? Who was he when Jesus first met him? What did he hope that God was about to do in the world through Jesus? We have to ask these questions, because once upon a time there was a light in Judas that caused Jesus to invite him into the inner circle.

It’s easy to love Mary. In her extravagant devotion; in her rejection of social convention; in her refusal to be put in her place, we see something strong; someone to admire. And it’s easy to hate Judas. In his bitterness and envy; in his dishonesty and betrayal, we see weakness, something to loathe.

In just a few minutes, as I invite us all to the Lord’s Supper, I will say these words:“The first time Jesus sat down to this meal, among those gathered there were one who would doubt him, one who would deny him, one who would betrayhim, and they would all leave him alone before that night was over—and he knew it. Still he sat down and ate with them.” Jesus sat down and ate with Judas.

Mary was faithful. Judas was not. But faithful or not, they remained his. And faithful or not, we remain his. On the days of our generosity, we are his. On the days of ours selfishness, we are his. On those days when we don’t even understand why we do the things we do, we are his. We are two sides of the same coin. And the that coin belongs to Christ. Thanks be to God. Amen.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed