Sunday, March 17, 2024 – Lent 5

First Congregational Church of Cheshire

© the Rev. Dr. James Campbell

John 12:20-33

Now among those who went up to worship at the festival were some Greeks. They came to Philip, who was from Bethsaida in Galilee, and said to him, “Sir, we wish to see Jesus.” Philip went and told Andrew; then Andrew and Philip went and told Jesus. Jesus answered them, “The hour has come for the Son of Man to be glorified. Very truly, I tell you, unless a grain of wheat falls into the earth and dies, it remains just a single grain; but if it dies, it bears much fruit. Those who love their life lose it, and those who hate their life in this world will keep it for eternal life. Whoever serves me must follow me, and where I am, there will my servant be also. Whoever serves me, the Father will honor.

“Now my soul is troubled. And what should I say—‘Father, save me from this hour’? No, it is for this reason that I have come to this hour. Father, glorify your name.” Then a voice came from heaven, “I have glorified it, and I will glorify it again.” The crowd standing there heard it and said that it was thunder. Others said, “An angel has spoken to him.” Jesus answered, “This voice has come for your sake, not for mine. Now is the judgment of this world; now the ruler of this world will be driven out. And I, when I am lifted up from the earth, will draw all people to myself.” He said this to indicate the kind of death he was to die.

When did Jesus know that he was Jesus? When did he understand that he was the Christ? Did he understand it at all?

This was a topic of discussion raised at last week’s sermon talk-back session. And when the question was raised, I chuckled because I knew that no one knows the answer, even if they claim that they do. It’s one of those questions that goes back to the beginning of the church - and has been the subject of a good many church fights.

Underneath that question - when did Jesus know that he was Jesus - is a much larger question. Because what we are really talking about is the nature of the Incarnation. In other words, how is it that Jesus of Nazareth is both fully human and fully divine at the same time? Now we say that “Jesus was both human and divine” rather casually, like we say “Pass the salt.” But when push comes to shove, what on earth does it mean to say such a thing?

It’s a very hard question to answer because the equation – fully human and fully divine – defies logic. So, Christians, since the beginning, have tended to favor one side of Jesus over the other. Either he was just a very good man who said some very wise things, or he was a divine superhero who can vanquish anything.

I think that most of the time, the church has tended to favor the divinity of Jesus. It’s just easier that way. He fills a bill because we humans need our heroes. And besides that, who wants a Savior who woke up on the wrong side of the bed or who cooked a bad meal or who had a stomach virus? And so, we talk far more about a Jesus who did miracles, and had a direct line of communication with the Almighty, and who even vanquished death, making him the ultimate superhero.

This tendency to favor the divinity of Jesus over his humanity goes back to the beginning. In the 2nd century there was a group of Christians called the Gnostics. They loved Jesus, but they just could not deal with his humanity. And so, they declared that Jesus was not really human at all. Instead, he only appeared to be human; he only appeared to have a body because how on earth could the divine be tainted with humanness? It made no logical sense. Well, the Gnostics lost the argument, and were eventually declared heretics. Their theology was consigned to the dusty pages of history. – Or was it? Because I think that some of their influence lives on in our discomfort with a fully human Jesus.

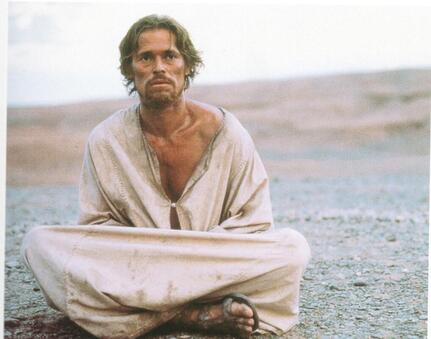

Back in 1998, a very controversial film entitled The Last Temptation of Christ was released. And boy, oh boy, did that film ever push some religious buttons! Why? Because it dared to portray the humanity of Jesus in an unvarnished fashion. The Jesus of this film was deeply human and, at times, deeply troubled. And his so-called last temptation was a hallucination he had while dying on the Cross, in which he imagined what his life might have been like had he married Mary Magdalene and raised a family.

Under intense pressure, Blockbuster Video (remember them?) would not carry it. People burned copies of the film in public displays of religious fervor. Whole groups of Christians were forbidden from viewing such blasphemy. These were people who would not entertain a Jesus who had doubts and fears, who felt love and desire, and who wondered where the road not taken might have led.

Today’s Gospel lesson presents a Jesus in which divinity and humanity are mixed together and on full display. In this story, we see a Jesus who is both directly connected to his Father in heaven, and a Jesus who is frantic and unfocused and emotional.

Jesus and his disciples were in Jerusalem for the Festival of the Passover. And by this time in his life, his fame had grown to the extent that he was recognized in public. Some Greek pilgrims had heard that Jesus was there and they wanted to talk to him. So, they went to Phillip, who, apparently was in charge of scheduling; who then went to Andrew, the social secretary. And together, they went to Jesus to ask if he would see if he would grant an audience with the Greeks.

But it was as if Jesus never even heard the question, because he doesn’t answer at all. Instead, in a seeming non-sequitur, Jesus speaks of dark and foreboding things. He makes an odd reference to wheat falling into the ground and dying before it rises as something new. He says that we have to hate our lives in order to find real life. And then, in a pivotal moment, Jesus cries out: “Now is my soul troubled.” Then the Voice of God speaks to him. Then Jesus speaks of judgment and crosses and salvation.

Notice that there are no neat categories here. Divinity and humanity are not parsed and separated. Instead, it is all a heady mix of feelings and emotions and thoughts all battling for attention.

It is because of passages like this one, and the one we read from the book of Hebrews today, that I have long since given up the idea that the passion of the Christ was only about the Cross. It seems to me that the passion of the Christ was about the whole of his life, as he tried to understand who he was and who God is and what was expected of him and how it all was supposed to work together. And it was that experience of life – his love and tears and fears and hopes and dreams and disappointments and faith – that saves us. Because it is God with us. God among us. God as one of us.

On a beautiful day last week, I took a walk over to Hillside Cemetery “to visit the ancestors,” as I like to say. I especially wanted to pay my respects to the Rev. and Mrs. Samuel Hall, the founders of this congregation. After I had spent a little time with the Halls, I wandered around some other parts of the old cemetery I had not been to before. In that wandering, I came across a very large marker with the name “Bristol” on it. I didn’t realize it at first, but I was actually on the backside of that stone. And so, it was the children’s names that I saw first. There was Lucy, who tragically died when she was two; and Edward who only lived to be seven; and then there was Edwin who made it all the way to nine. Then I rounded the marker and saw the names of the parents: Jesse, the father, who died at forty-one. But it was the mother’s name that really grabbed my attention. Her name was Fanny, and she lived to be seventy-six. And then it struck me that Fanny had lived long enough to bury her whole family. And then Fanny lived without all of them for four more decades. And I thought about her grief and I thought about this passage and I wondered: did Fanny Bristol need a Savior who was a superhero, who was always in control? Or did Fanny Bristol need a Savior, who was, in the words of the prophet Isaiah, “a man of sorrow who was acquainted with grief.”[1]

I do believe in the divinity of Jesus. But I connect with and trust his blessed humanity. Because in his humanity, Jesus knows first-hand the pain of loneliness and of being misunderstood. He experienced deep disappointment and burning anger. He understands the nagging regret of “what might have been.” He knows the sting of bullies and the fear of tyrants and the awful silence of God. And he knows what it’s like to die.

And therein lies his power to save someone like me. Because it is in his humanity that we see ourselves. And it is in his divinity, that we hope for what yet might be.

So, blessed be the Son of Man. And blessed be the Eternal Christ. And blessed be the Cross, where all things come together.

[1] Isaiah 53:3

RSS Feed

RSS Feed