Easter Sunday, April 12, 2020

First Congregational Church of Cheshire

© the Rev. Dr. James Campbell

Mark 16:1-8

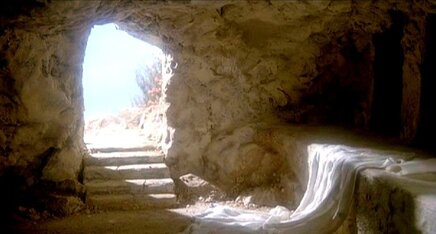

When the sabbath was over, Mary Magdalene, and Mary the mother of James, and Salome bought spices, so that they might go and anoint him. And very early on the first day of the week, when the sun had risen, they went to the tomb. They had been saying to one another, ‘Who will roll away the stone for us from the entrance to the tomb?’ When they looked up, they saw that the stone, which was very large, had already been rolled back. As they entered the tomb, they saw a young man, dressed in a white robe, sitting on the right side; and they were alarmed. But he said to them, ‘Do not be alarmed; you are looking for Jesus of Nazareth, who was crucified. He has been raised; he is not here. Look, there is the place they laid him. But go, tell his disciples and Peter that he is going ahead of you to Galilee; there you will see him, just as he told you.’ So they went out and fled from the tomb, for terror and amazement had seized them; and they said nothing to anyone, for they were afraid.

One of my treasured possessions is an antique secretary that my mother gave to me many years ago, when I graduated from college. This secretary was not passed down from one generation of her family to the next. Instead, it came to us like most of the things in our house. It was the product of my mom’s keen eye and her absolute devotion to a good bargain.

She dragged it home one day and proudly announced that she had only paid $15 for it. I remember that my father scoffed when he saw it because, as he said, it didn’t look like it was worth $15. And quite frankly, it didn’t. That secretary was covered by 15 layers of black paint. But like I said, my mom had a keen eye. And she was sure that underneath all of those layers something simpler and far more beautiful would be found. The harsh chemical process of stripping it down would reveal that.

Stripped down. That’s how life feels right now, doesn’t it? Trauma has a way of stripping us all down to what is essential. Crisis clarifies what really matters; and in the process, reveals to us what is truly beautiful. In the midst of this world-wide pandemic, what really matters, we have discovered, are our relationships and families and shelter and food and community. These things are suddenly no longer the afterthoughts of our perfect lives. And all those superfluous layers which we think are so important – our preoccupations with political wrangling and social climbing and mindless spending are suddenly exposed for what they really are – just so many layers of old paint.

Stripped away. Now I will be the first to admit that I don’t necessarily like this process of stripping away. And I especially don’t like what has become of Easter this year with everything stripped away. You see, when it comes to Easter, I like all those layers. I love the drama and the pageantry and the music and the flowers and the churches full of people. But this year, I proclaim the empty tomb in an empty church, to people huddled in fear behind locked doors. And I don’t like it.

But I also suspect, in this odd and disconcerting time, that we are now as close as ever we can be to that first Easter. That first Easter was not marked by full churches and glorious music and festive brunches. Instead, its hallmark was something called “terror and amazement.”

The Gospel of Mark is the oldest gospel and thus Mark’s account of the Resurrection is the first. But it’s a bit misleading to even say that Mark has an account of the Resurrection, because what he really offers us is a description of its aftermath. And his account is really short. It’s only eight verses long and has a very unsatisfying ending. Who ends a gospel with fear?

Mark’s ending was so unsettling to some anonymous monks in the Middle Ages that they added several other triumphant conclusions to this Gospel. You can read both of them in your Bibles; along with footnotes that indicate that neither of these happier endings is original. Meaning that Mark meant to end his Gospel with a very human reaction to trauma.

Early on Sunday morning, Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James, and Salome went to the tomb, carrying the spices they had purchased in order to anoint the body of Jesus. As they walked along, they wandered out loud who would roll the stone away for them. But when they arrived, the stone had already been moved. And that was unsettling. But more unsettling still was the presence of an odd young man, dressed in a white robe, and sitting on the right side of the slab where the body of Jesus had been. And that just frightened them. The young man must have seen their fear and so he tried to calm them. “Do not be alarmed,” he said, “You are looking for Jesus of Nazareth, who was crucified. He has been raised. He is not here. Look, this is the place they laid him. But go, tell his disciples and Peter that he is going ahead of you to Galilee; there you will see him…”

The young man’s speech didn’t seem to work because, we are told, immediately afterwards the women were seized with what the Greek text calls “tromos” and “ecstasis” – trauma and ecstasy. I imagine bodies shaking, minds reeling, mouths dry, cold sweat – all the classic signs of being terrified. They were terrified on Easter Sunday.

+++

As I said, the Gospel of Mark never presents the Risen Jesus to us. The other Gospels do, claiming that people actually saw him - in the garden, on the Road to Emmaus, in a locked room. They not only saw him, but they touched him and ate with him and listened to him. But in Mark, there is only a promise. The young man who told them that Jesus had been raised also told them where they could see that for themselves. He said: “Go tell his disciples and Peter that he is going ahead of you to Galilee; there (out there in the future, in the living of your lives, in your everyday) you will see him, just as he told you.”

And so they set out on a journey into the rest of their lives, into the unknown of tomorrow, into a world dominated by a hostile Empire that crucified their Lord. They went, hoping, wondering if this outlandish promise could possibly be true. But they went, because the promise was all they really had.

That’s all we really have too. All the other layers of what it means to celebrate Easter have been stripped away. Even coming to church has been taken from us. But we are not bereft this Easter. We are not left on our own this Easter. Like the women, we have the promise that the Risen Christ goes before us into whatever it is that frightens us. It is there that we will find him.

Perhaps this year we can actually grab hold of that promise. Because if this were just like any other Easter, with bonnets and brunches and chocolates and friends, would we really hear that message? Would we come to church and leave unmoved by a message meant to move the whole world? It’s possible. All those layers might get in the way and obscure the truth that is meant to set us free.

If there is any blessing in this empty church on Easter Sunday, it’s this powerful reminder: one does not come here to find the Risen Christ. He was not in the tomb. And he will not be contained in this or any other sanctuary. He’s out there, ahead of us. He’s out there, in the days of our isolation and fear and boredom yet to be. And he is out there, in those days beyond this crisis. There we will see him.

We are left to imagine that an empty tomb and a strange young man did not quite convince the women that Christ was alive. It was their going to Galilee that did that. They got there to find what we find - that there is no place on this whole earth, no fear so stark, no valley so deep that the Risen Jesus will not appear when we need him most. And when he does, we join the faithful women in proclaiming: The Lord is risen; he is risen indeed!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed